|

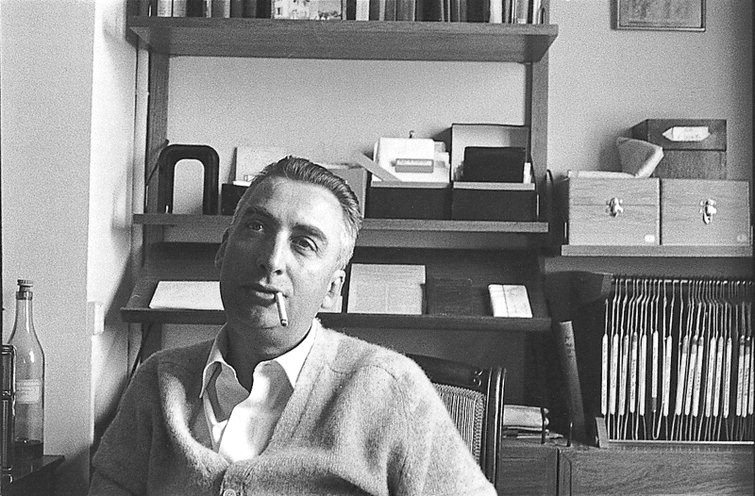

| The good, grey poet in Washington, D.C. in the mid-1860s, as photographed by Matthew Brady. |

One could make an argument that — in spite of the achievements of Wheatley, Longfellow, Dickinson and Poe, among others — American poetry truly begins with the 1855 publication of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. In large part, that argument would rest on whether you define a national literature as merely having its origin in a given location, or whether it must reflect and embody the nature and spirit of its homeland. Whitman is a great cataloguer, a voracious explorer of the things that filled up the world around him, and one major part of that was the soundscape of a nascent America, something that had never occurred to his predecessors, who measured themselves against continental aesthetics.

While this goal fits beautifully within our understanding of the sonic and performative origins of poetry, and even more so the symbolic role song (in its myriad guises) plays within Whitman's poetics, we must understand that his attempts, while radical for their times, were still somewhat constrained by the ongoing evolution of American English. Lew Welch (who we'll read later this term) speaks briefly to this when he observes that:

Now, William Carlos Williams and Gertrude Stein and Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald and Sherwood Anderson were working on [authentically rendering American speech] around 1908 on. The reason that they could start working with that at this time was that for the first time in history, the first time in the world, there was such a thing as American speech. Whitman had no language to write in. If you read Whitman with this in mind you’ll notice these incredibly clumsy frenchified funny words. It’s just amazing that the man wrote such great, you know, really world poetry, when he had no language to work in. He just had a hodgepodge. He’s working in the rubble of Europe and he’s sitting in the smokes of industrial America. Wow, how he ever put anything together out of that is a sign of his true greatness.

In other words, poetry doesn't catch up to language (and vice-versa) until we get to the 20th century, but without the heroic efforts of Whitman, we might have waited a lot longer.

Our readings for Tuesday will focus primarily on Whitman's magnum opus, "Song of Myself," with three other poems added to the mix. While we'll address these poems in a general sense, you'll also want to keep an eye out for their aurality and orality: their internal music and the sounds they document.